Chapter 1- The Preparation

ARTICLE I-THE REMOTE PREPARATION

1. God's Design

God frequently punishes sinful man by delivering him up to a reprobate sense (Rom. 1 :28) and to the tyranny of the passions of his heart (Rom. 1 :24) as the reward of his contempt of divine love. When the whole world shall renounce Christ and reject the authority of His Church, when men shall say like the Jews of old, we will not have this man to reign over us, (Luke 19:14), We have no king but Caesar, Jn. 19:15), the vengeance of God shall be swift and terrible. His treatment of the world. shall be like to that of individuals. He shall respond to its criminal desires, which stifles the love of those saving truths, by the light of which the ship of state can alone be safely piloted through the siren dangers to which it is constantly exposed. He shall deliver it up to the man of sin who shall consign it to the darkness of vice and error since it rejected the light of truth and virtue. (2 Thes. 2). Satan shall have universal sway for awhile over all nations.

The Holy Catholic Church, which has fought the battles of Christ for eighteen hundred years, is therefore destined to pass through a persecution compared to which those that she has suffered up to the present time are insignificant. St. Augustine classifies them under three general headings. The first he calls violent, on account of the cruelty with which the early Christians were treated by the Roman Emperors, while at a later period the Church suffered from the deception of false brethren, a trial much more insidious than the former, as it was more dangerous. But the persecution of Antichrist will combine both forms and will consequently prove more redoubtable than when one form only had to be contended with.

2. Who is Antichrist

The word "Antichrist" is composed of two Greek words, anti, against, and XPISTOS, Christ, which signifies against Christ. He shall be supremely inimical to Jesus Christ. This name, or rather surname, is given him by Holy Scripture, which calls him also "the Man of Sin," "the Son of Perdition," (2 Thes. 2:3), "the Beast that ascended out of the abyss," (Apoc. 11:7), "the abomination of desolation." (Dan. 9:27).

The Fathers and theologians regard him as the most impious of men. As for his family name, that is not known; still it is known that the number obtained from the addition of the Greek letters with which it is written will be 666. "Behold wherein wisdom cometh," says St. John in the Apocalypse, "let him that understands count the number of the beast, for it is the number of the man." It is the number 666. Many other names are composed of this number. St. John calls this number "the number of the man" because the number 6, which designates the day on which man was created, enters into its composition in three different ways, namely, in its concrete form, 6, and as a multiple of 10, 60, [and as a] multiple of 100, [600] equals in all, 666. This triple ratio of 6 points out the threefold prevarication and malediction of Satan, Antichrist's cruel master and tyrant. Satan prevaricated and was cursed in heaven; he prevaricated and was cursed in the serpent in paradise. Finally, he will prevaricate a third time, and will be cursed in Antichrist, whom he shall employ to allure the world and drag it into the abyss. (Cornel. - a Lapide).

The contemporaries of Antichrist who are enlightened by the Sacred Scriptures will alone be able to discover the solution to this problem. Such was the case with those who were contemporary with Jesus Christ, of whom Antichrist will be the counterpart. The Jews knew full well that Christ would come, but they ignored the name that He would bear.

3. Will There be an Antichrist

Some have thought that the word Antichrist is only a generic term by which all the enemies of Christ are designated, a word comprising in its signification all heretics, schismatics, apostates, infidels - in a word, all the impious or antichristian empire. St. John seems to hold this opinion when he says, "Even now there are become many Antchrists. He who denieth that Jesus is the Christ, this is Antichrist." (1 In. 2:18-22). But that this supposition is erroneous is proved by the context of the same epistle. "Little children, it is the last hour; and as you have heard that Antichrist cometh, even now there are many Antichrists."

Let it be remembered that in the Greek or original text, the article 'O is employed in connection with Antichrist in the first instance, and not in the second, and the Greek article serves to determine persons and things; whence, it follows that St. John did not mean that all the enemies of Jesus Christ were to be comprised in one generic term expressed by the word ."Antichrist". On the contrary, he very succinctly, but clearly, distinguishes Antichrist personally from all the other adversaries of Christ.

Moreover, the Sacred Scriptures speak of Antichrist in various places as being a particular person or individual. "The Man of Sin," "Son of Perdition," terms such as these cannot mean a collective body since the individual is specifically pointed out, while it is easy to explain why St. John employs the same word to distinguish the enemies and adversaries of Christ. The similitude of tendencies and actions suffices to justify the identity of names. The priests, prophets, and kings of the old law were called "Christs". This, however, did not hinder the Jews from believing in the coming of Christ, the Anointed par excellence, source of all sacerdotal, prophetic, and royal unction. And is not the same thing true of Antichrist and the Antichrists, that is, of the enemies of Christ? But there shall come an Antichrist of whom all the others are only the precursors. And this Man of Sin will combine in himself all the malice collectively found in all the others. All the Fathers and theologians unanimously concur in this belief as to Antichrist's individuality. And

conseqeuntly, his personal existence and future event must be considered as an object of divine faith, such as stated by Suarez and Bellarmine.

4. Antichrist Foretold and Prefigured

Before the coming of our Divine Saviour there were many prophecies and figures given of Him. It shall be the same for Antichrist. The prophet Daniel speaks of him in a literal and mystical sense in three different chapters, namely, 7, 9, and 11, while St. Matthew chapter 24, St. Mark chapter 13, St. John chapter 5, and St. Paul in his 2nd Epistle to the Thessalonians chapter 2, St. John in his 1st and 2nd Epistles, and especially in the Apocalypse chapter 13; etc. tell us of his future or coming event.

Since he will be the incarnate evil and according to the expression of St. Ireneus (c. 28, lib. 5), the maximum of malice, "recapitulatio universae iniquitatis," the Fathers are justified in applying to him all the passages in the Sacred Scriptures in which there is question of the actions of God and His Church.

We are therefore justified in asserting that Antichrist has been prefigured by the persecutions of the Church, by all the enemies of Jesus Christ, whatever may have been the form under which they have existed. Cruel persecutors such as the Caesars represent his future cruelty towards those who will remain faithful to God. Hypocritical persecutors such as Julian the Apostate are typical of his deception and consummate hypocrisy. Heresy and schism, but above all the incredulity and impiety of our time, are the prelude to the great Apostasy into which he will cause many to fall. Finally, those who give themselves up to their passions and who drink from the pool of iniquity form themselves to his image and likeness, which explains the words of St. Paul when he said. "For the mystery of iniquity already worketh." (2 Thes. 2:7).

ARTICLE II-ACTUAL PREPARATION

As the mystery of evil is always in labor, it is useful to take a passing glance at the city of actual evil, in order that we may better understand how our contemporaries prepare the way for the coming of the "Man of Sin."

1. Political Preparation

A few centuries ago it was quite a difficult problem for theologians to explain how Antichrist would bring the world under his political and religious dominion. But in our time it is easy to conceive the possibility of such a feat.

Communication with all parts of the world is now rendered easy by means of steam and electricity. People of different nations intermingle. The remotest parts of Asia and Africa are no longer impenetrable; they are on the point of entering into the European movement. The difference of manners and customs tends to disappear; every obstacle to a universal fusion of ideas seems to vanish; small nationalities are absorbed by the greater ones, which in turn may one day become the prey of a more powerful one. And such a preponderance is now quite manifest as regards resources, of which the Jews are the rulers, while there are combined forces secretly working to pervert public opinion throughout civilized nations and destroy Catholic influence.

Evidently we are rapidly drifting towards the time when all nations will blend in one universal fusion of political unity. The great conqueror of modern times seemed to realize this when he said: "In fifty years hence, Europe will be either Cossack or a republic." Hence the possibility of the political empire of Antichrist is evidently quite feasible.

2. Religious Preparation, Both Intellectual and Moral

But how shall he deprive the world of Christianity and have himself adored as God? Alas, it is only too true that the minds and hearts of men are admirably disposed for revolution and consequently ready to accept and bear the cruel yoke of such a tyrant.

Revolution as the word itself implies means a subversion, but a subversion of all that is true, good, beautiful, and grand in the universe. It is the subversion of religion, representing its dogmas as myths and its moral teachings as tyranical. It is the subversion of authority. Licentiousness under the name of liberty becomes the order of the day; each one is invested with the right to govern himself.

It is the subversion of reason: and do we not find leading minds in some of the most enlightened nations denying the principle of contradiction and maintaining the absolute identity of all beings?

Revolution is therefore essentially destructive, and it becomes cosmopolitan by the action of secret societies scattered throughout the world. Is it not true to say that the "mystery of iniquity" is prepared in secret revolutionary dens?

But it does not suffice to destroy; it is absolutely necessary to build up again. The world 'cannot subsist long in a vacuum. It must have a religion; it must have a philosophy; it must have an authority. Revolution will furnish all these.

Instead of the reasonable and supernatural religion of Jesus Christ, Revolution will preach Pantheism. The God-humanity will impart the theurgic spirit and thus lead men to adore the demon as the author of universal emancipation. "Haste to my aid," exclaims one of the most rational of revolutionists. "The faith of my fathers made thee the enemy of God and His Church, but as for me I shall promulgate thy doctrine and ask thee for nothing." .

"Haste, Satan, haste, thou who art calumniated by priests and rulers; haste that I may press thee to my heart; we have known each other long. Thy works, a cherished one of my heart are not always good and pleasing, but they give tone to, the universe and save it from being absurd. What would justice be without thee? An instinct. What would reason be? A routine. What would man be? A beast. Thou alone dost impart prosperity to all; by thee riches are enobled. Thou art an excuse for authority and the seal of virtue. Hope on proscribed one! The only arm that I can wield in thy service is my pen, but that is worth millions of bulletins! (Proudhon quoted by Bishop Dechamps in the Christ and Antichrist) .

What frightful immorality must follow in the train of this shameless prostitution of religion! Never has the threefold concupiscence made greater ravage among mankind. And this is the religion sought and hoped for as the cherished boon of the aspirations of our modern free thinkers.

To our Christian philosophy, the honor of humanity's revolution will substitute a babel of extravagant and absurd ideas. Instead of a mild and efficient authority consecrated alike by Church and state, despotism and anarchy will rise up and contend for the shreds of religious liberty and human policy.

Alas, it must be confessed that the advocates of error are on the increase; the number of depraved characters become more and more numerous. And if the state of perversion continue for a while longer, Antichrist may come, for he will find the world prepared to receive and serve him.

a homines ad servitutem promptos -- O man, how prompt to enslavement Tacitus

_______________________________________

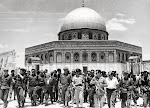

Palestine Cry: The path to war in Iraq

_______________________________________

Also see this:

This talk is on the Twin Towers demolition. The tower collapses were the most deadly, traumatic events of the September 11th attack. If the collapses were caused by ...

911research.wtc7.net/talks/towers/text/index.html